Running and Age

We run to learn. This means that as we age, nothing changes. Until you are ready to surrender.

Nothing changes because the hunger is still there. The craving for intensity. Fear is still there too, because it’s inescapable that physical resilience degrades with time, and injuries heal more slowly, which means the consequences are more severe and the stakes are higher when we head out sleepy-eyed for the morning jog or toe the starting line for an important race or disappear into the wilderness in pursuit of enlightenment.

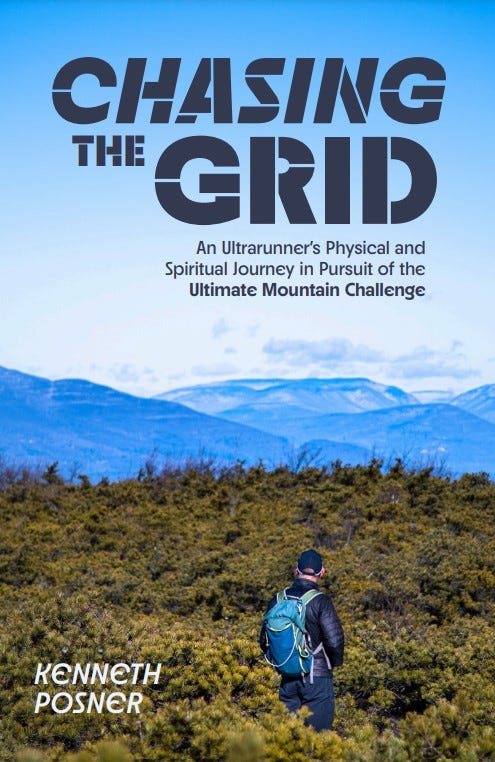

Chasing the Grid is the story of how I took on a peak-bagging challenge in the Catskills Mountains. The action starts when I was in my mid-50s and still felt young. I’d just come off a period of training and racing which was intense – why, I’d set lifetime PRs for every distance from one mile to one hundred, running even faster than I had when in college, and then I went out on multi-day endurance tests, like the 294-mile Badwater Double in Death Valley and the 350-mile Long Path in New York, where I broke the existing records. People whom I respected took note of these accomplishments. You can imagine my pride. The brimming confidence. For a shot at more distinction I would have undergone any test or trial.

Of course, I knew age was looming. That speed could not be sustained indefinitely. But I was determined to fight age with every resource at my disposal. I hungered to run every distance faster, if only by a fraction of a second. And why not? Why not expend all our energy to see what we can do?

After all, it’s not like anyone runs for health or longevity. They may say that, but they don’t mean it. Tell me why you care about yourself at age 85 or 90 or 95, assuming you’re still mobile and clear of mind and even marginally productive. Tell me how that probability-weighted future state could possibly matter more than what you do. Right. Now. No, we run not for health but for the intensity. We’re hungry for pain, actually – and the contrast with comfort – because that’s how we learn. About ourselves. About our capabilities. Our capacity to persevere. When we were young, we had to break through perceived limits to find reality. The imperative to understand our capabilities does not dissipate with age. Unless you no longer care to exercise them.

Now, pain signals risk, and f you do enough hard running, you are sure to suffer injuries. These are inescapable. Incidentally, following my string of personal bests, I developed chronic tendinitis in my ankle. Undeterred, I kept running. Did, maybe, one ultramarathon too many. Now the ankle cried out when I tried to jog. My sports doctor told me to take a 3-month break. 3 months turned to 6 months and still the ankle tendon burned, even while walking slowly on the treadmill.

I dragged myself to work and sat in my windowless office and tried to focus on the analysis and presentations which are my stock in trade. Thoreau’s warning came to mind — that the majority of men lead lives of quiet desperation. Suddenly I realized that without a new passion, that group would soon include me.

Which is why the Catskills peak-bagging exercise was so intriguing. Instead of running hard, I could saunter along the trails and work on the list of peaks at an easy walking pace. The experience felt reminiscent of ticking off the miles in an ultramarathon, only the progress was measured in days and weeks instead of hours. The project captured my imagination. It gradually turned into an obsession. After focusing on work for over thirty years, I suddenly felt an insatiable appetite for the outdoors, no matter the weather or how I was feeling. This peak-bagging project became the most important priority of my middle-aged life. Maybe it was my mid-life crisis (or one of them), but regardless I saw so much in the mountains and learned so much about myself that by the time I’d finished, I had become a radically different person.

My story is an example of what business strategists call a “pivot.” To keep moving, I shifted from fast-paced racing and ultra-running to slower-motion hiking and peak-bagging, yet by choosing a new set of goals I was able to sustain the intensity and keep learning.

You might think of aging like a military contest, with the understanding you will not win every battle. Soldiers understand the need to keep shooting and maneuvering, even after suffering a defeat, which is why they say, “Stay in the fight.” In other words, don’t let those nasty voices in your head talk you into giving up. If you can’t run, then walk. If you can’t walk, then go to the gym. If that doesn’t work, try cold showers or take up pistol shooting or sit in place and hold your breath (practice breathwork).

As for me, it’s now nearly ten years since my adventures in the Catskills Mountains. The ankle did heal eventually, and I resumed my running practice. Recently I completed the Ft. Worth Cowtown Marathon, which was my 115th race of marathon or ultra distance. While my time wasn’t particularly impressive, I ran the race barefoot and in a cow costume, which made for a distinctive experience, and a lot of fun. The children squealed “Go barefoot cow!” and their parents called out “Keep mooovin’.”

In August 2011, I heard the legendary mountaineer and ultrarunner Marshall Ulrich give a talk before the Leadville 100-mile ultramarathon. He told the crowd, “don’t stop setting goals even as you get older.” My kids, then 7 and 10 years old, were with me. I took them up to meet Marshall and told them to listen to his advice. Which I took to heart myself. While I continue to race as often as I can, I’ve also committed to a lifetime goal of climbing 1,000 mountains barefoot (the count is currently 489). Why barefoot? As I age, I figure it’s smart to stay as natural as possible.

Regardless of your own particular modalities and style, I hope you keep moving. Young people like me are watching. We need the inspiration.